When Armenian artist Aram Galstyan first decided to compile a book on Soviet mosaics, he was unsure that he was going to find anyone willing to publish it.

“I didn’t know if anyone was interested in taking on such a risky project, especially since these books aren’t exactly destined to become bestsellers’, he says.

Luckily for him, Frank Böttcher, the editor of Lukas Verlag publishers, is a great admirer of socialist art, and was keen to publish the 10 years of material that Aram had gathered with Rostock-based professor Katja Koch.

“We didn’t want our pictures to just stay on our computers”, says Aram, “we were saddened by the decaying state of these artworks and wanted to preserve their memory.”

Coded signs of resistance

Mosaics featuring the same iconography and symbolism may come up repeatedly when researching the topic, but one of the focuses of the book is how the artworks are not merely propagandistic, but possess creatively coded signs of resistance to Moscow centrism.

The further away from the centre of power, the less control artists were under and the easier it was to experiment. It was this understanding that guided Katja and Aram further East on their trips.

Aram cites a work by Satar Aitiev in Bishkek as a prime example: “It has absolutely nothing to do with socialist realism. Rather, it has more touches of Impressionism, which was quite shocking at the time.”

He also recalls the Republican Hospital in Yerevan, and observes that the women on the facade’s mural look more akin to angels floating in the sky than Soviet midwives.

Grassroots restoration

Yerevan itself is full of many works, however it was in his hometown Yeghegnadzor, that Aram became inspired to put down his lens and start a preservation campaign.

“There aren’t many mosaics in the region, but there is one particularly interesting piece – a cascade that was built for the 700th anniversary of the University of Gladzor.”

The mosaic was in a dilapidated condition for almost two decades. “Nobody was interested in it, there were rumours that it was going to be demolished. Eventually it was decided that it would be replaced with a floral arrangement in Armenia’s tricolor. I immediately jumped on a plane and met with the mayor of the city”, he remembers. Aram managed to obtain permission to restore the mosaic, but on one condition, that the local authorities did not spend a penny.

A close friend of Aram’s, Gevorg Babakhanyan, was trained in art restoration and had just returned to Armenia after studying in Venice. “He offered to restore the mosaic without a fee. There were many good people who sponsored it though, from locals, to my friends and colleagues in Germany.”

Ideological adaption

Aram notes that many pieces have been destroyed by individuals who did not realise their historical value. After the 2018 revolution,the government promised to preserve the country’s cultural heritage, and to condemn its destruction as a violation of human rights. With regards to ‘decommunization’, no process was ever introduced at a legislative level.

Throughout their travels, the pair encountered symbols that had been plied out or damaged and eroded. It was in Turkmenistan that Aram noticed something peculiar – that many Soviet-era mosaics were well-maintained, but redesigned with new symbols of the independent country.

“Overall, the presence of mosaics can be dependent on the economic situation of that area. In the provinces, there aren’t as many new buildings, so many of the old Soviet ones remain. Unfortunately though, the works in these areas tend to not be so big or as important as those that were in urban areas”, he says.

The artist also drew parallels on a political level: “In Belarus: there is a very close connection with the Soviet era, so many works of art are protected by the state”

Public artwork, private space

Aram notes how formerly-public artworks also shape-shift into an untouchable role in newly-privatised spaces.

“Security officers would forbid us from shooting. We often came across police who threatened us with arrest and forced us to delete our photos. In other words, we fell victim to arbitrary and incomprehensible, illogical prohibitions.”

While artworks are being cordoned off and hidden from the public, collecting data on them also proved to be difficult for the pair, to the point that it would stall their work on the book.

Despite the difficulties in compiling such a comprehensive guide, it hasn’t put Aram off from considering a future project, in which he hopes to photograph Soviet mosaics in Russia, travelling from Rostock to Vladivostok.

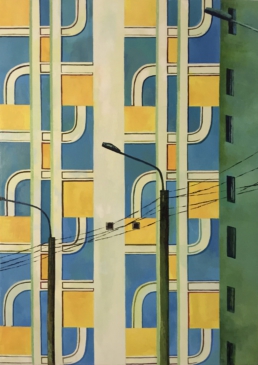

In the meantime, he has been using his photo collection as a source of inspiration in his own work as an artist.

“In Yerevan, I was amazed at the conditions of the apartments after privatisation, and the complete absence of state control. Even though the building had lost its uniform character, something inspired me that seemed quite magical”, he says.

He took to the canvas and has created a series of works on residential buildings and hotels which can be viewed here.

Aram is happy to see that he is not the only one inspired by socialist architecture and art:

“It is encouraging that there are more and more initiatives by young people who reject iconoclasm and seek to preserve the cultural heritage of that time.I have high hopes.”